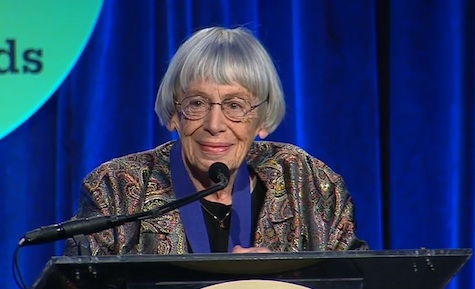

Last night at the 2014 National Book Awards in New York City, Neil Gaiman presented science fiction and fantasy legend Ursula K. Le Guin with the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, an honor that has previously gone to such luminaries as Joan Didion, Ray Bradbury, and Toni Morrison.

Gaiman spoke of the debt he owes Le Guin, who was a major influence on him as a young writer, while Le Guin’s acceptance speech highlighted the importance of the award as a recognition of the place of science fiction and fantasy in literature. She also called upon the next generation of writers to push for the liberation of their art from corporate demands and profiteering.

Before yesterday, Gaiman said, he had spoken to Le Guin only once: “Or, actually, more to the point, Ursula had only ever spoken to me… once.” The two met at a fantasy convention in the Midwest 21 years ago, when they shared the same elevator and Le Guin asked Gaiman if he knew of “any room parties” happening that night (he did not, to her disappointment).

Such a short exchange felt very odd, continued Gaiman, because Le Guin had been “talking to me for at least the previous 22 years.” At age 11, he bought—with his own money, no less—a copy of Wizard of Earthsea, and discovered that “obviously, going to wizard school was the best thing anybody could ever do.”

He bought the rest of the books in the series as they appeared, and in doing so discovered a new favorite author. By age 12, Gaiman was reading The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin’s 1969 novel about the gender-shifting inhabitants of the planet Gethen. As an English boy on the cusp of teenagehood, Gaiman said, the idea that “gender could be fluid, that a king could have a baby—opens your head. It peels it, changes it.”

Gaiman learned to write, intially, by copying the styles of other writers—C.S. Lewis, G.K. Chesterton—and figuring out “how they did it.” But he couldn’t figure Le Guin out, he said, because “her style was so clean; her words, so precise, and well chosen.” So, he cheated: He found essays Le Guin had written about her process and the craft of writing, for those who were interested. “I was 21 or 22, and I knew that I wanted to be a writer more than anything in the world, and dear God, was I interested.”

“I learned from her the difference between Elfland and Poughkeepsie,” Gaiman continued, “and I learned when to use the language of one, and when to use the language of another.” He learned about the usage of language, and its intersection with issues of social justice and feminism. Starting out on Sandman, Gaiman began to ask himself, whenever a new character appeared: “Is there any reason why this character couldn’t be a woman? And if there was no reason, then they were. Life got easy.” Le Guin, Gaiman went on, “made me a better writer, and I think much more importantly, she made me a much better person who wrote.”

Le Guin is a writer who transcends genre, writing science fiction, fantasy, and mainstream fiction; writing for children, adults, and all those in between; dealing deftly with both huge, cosmic ideas and everyday issues on a human scale. She is “a giant of literature, who is finally getting recognized,” Gaiman concluded, “and I take enormous pleasure in awarding the 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution for American Letters to Ursula K. Le Guin.”

Large as she may loom in literature, Le Guin is small in stature, and noted, upon taking the stage to thunderous applause and adjusting the microphone, that “I seem to be shorter than most of these people.” But her presence filled the ballroom as she spoke of “accepting the award for, and sharing it with, all the writers who were excluded from literature for so long, my fellow authors of science fiction and fantasy—writers of the imagination, who for the last 50 years watching the beautiful rewards go to the so-called realists.”

“I think hard times are coming,” Le Guin continued, “when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries—the realists of a larger reality.” She stressed that writers must remember the different between “the production of a market commodity and the practice of an art.” Sales strategies and advertising revenue should not dictate what authors create, and both publishers and authors should take responsibility for protecting art and providing access to readers.

Books are not just commodities, Le Guin emphasized. “The profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable.” She paused, and then continued, wryly: “So did the divine right of kings.” Human beings have the ability to resist any human power. Resistance and change often begins in art, and “very often, in our art—the art of words.”

Le Guin ended her speech with a powerful call for artists and publishers to push back against the commodification of literature. “I have had a long career and a good one. In good company. Now here, at the end of it, I really don’t want to watch American literature get sold down the river. We who live by writing and publishing want—and should demand—our fair share of the proceeds. But the name of our beautiful reward is not profit. Its name is freedom.”

Watch Le Guin’s entire speech below: